Spirit-Infusing

ARTIST: Shen Lu

SOLO EXHIBITION 16/06/2024-20/06/2024

Spirit-Infusing : Textiles, Algorithms, and Life

Spirit-Infusing

16/06/2024-20/06/2024

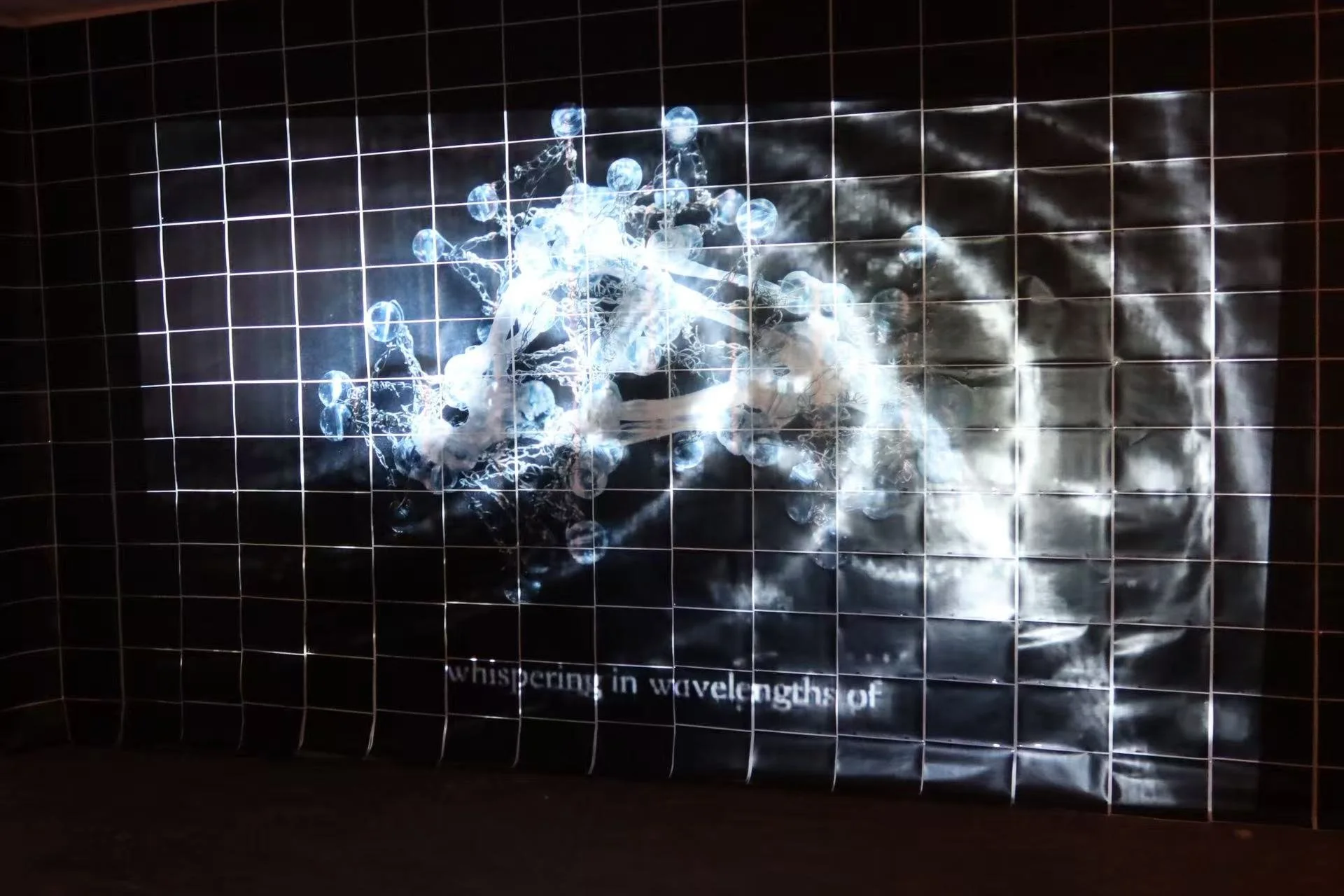

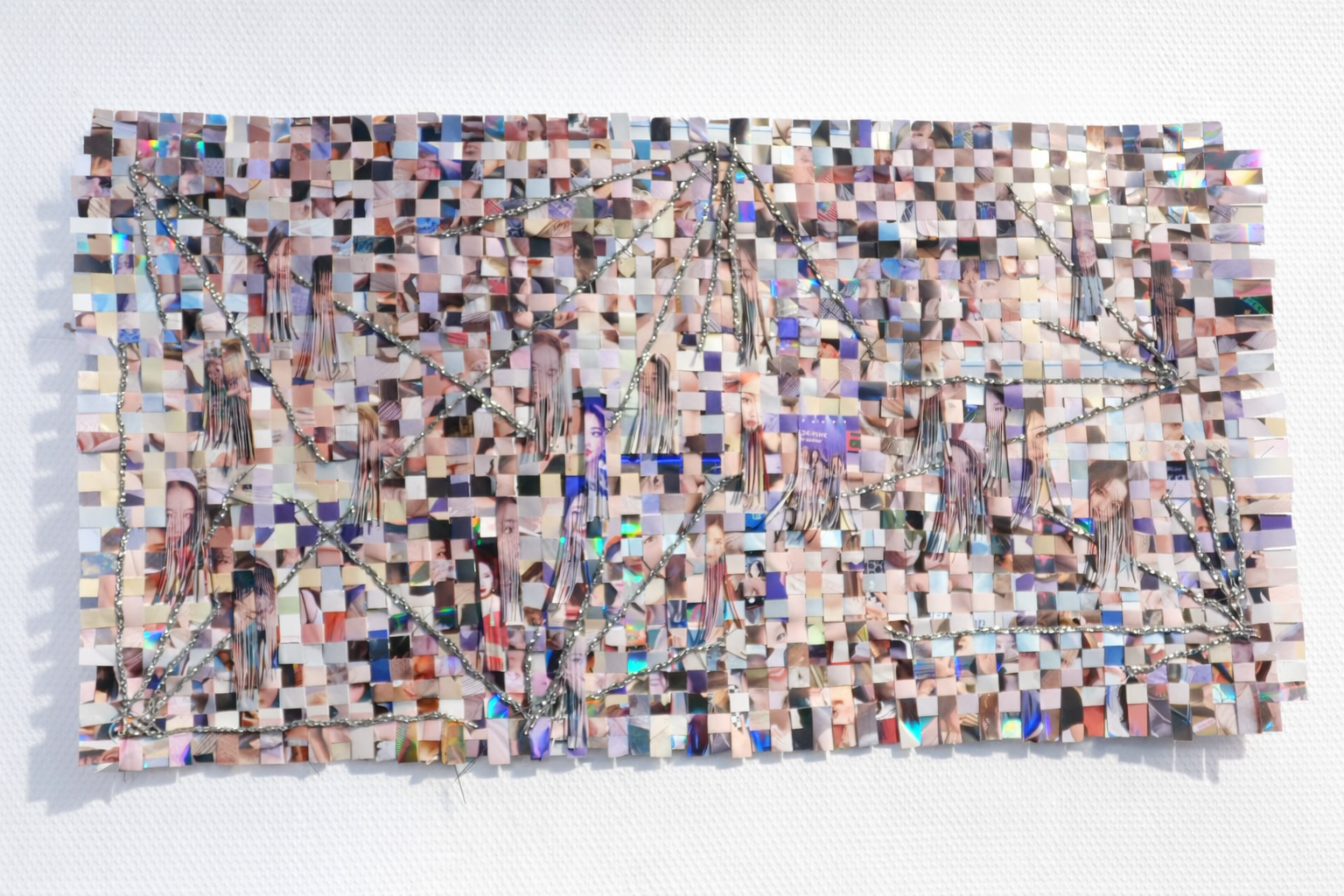

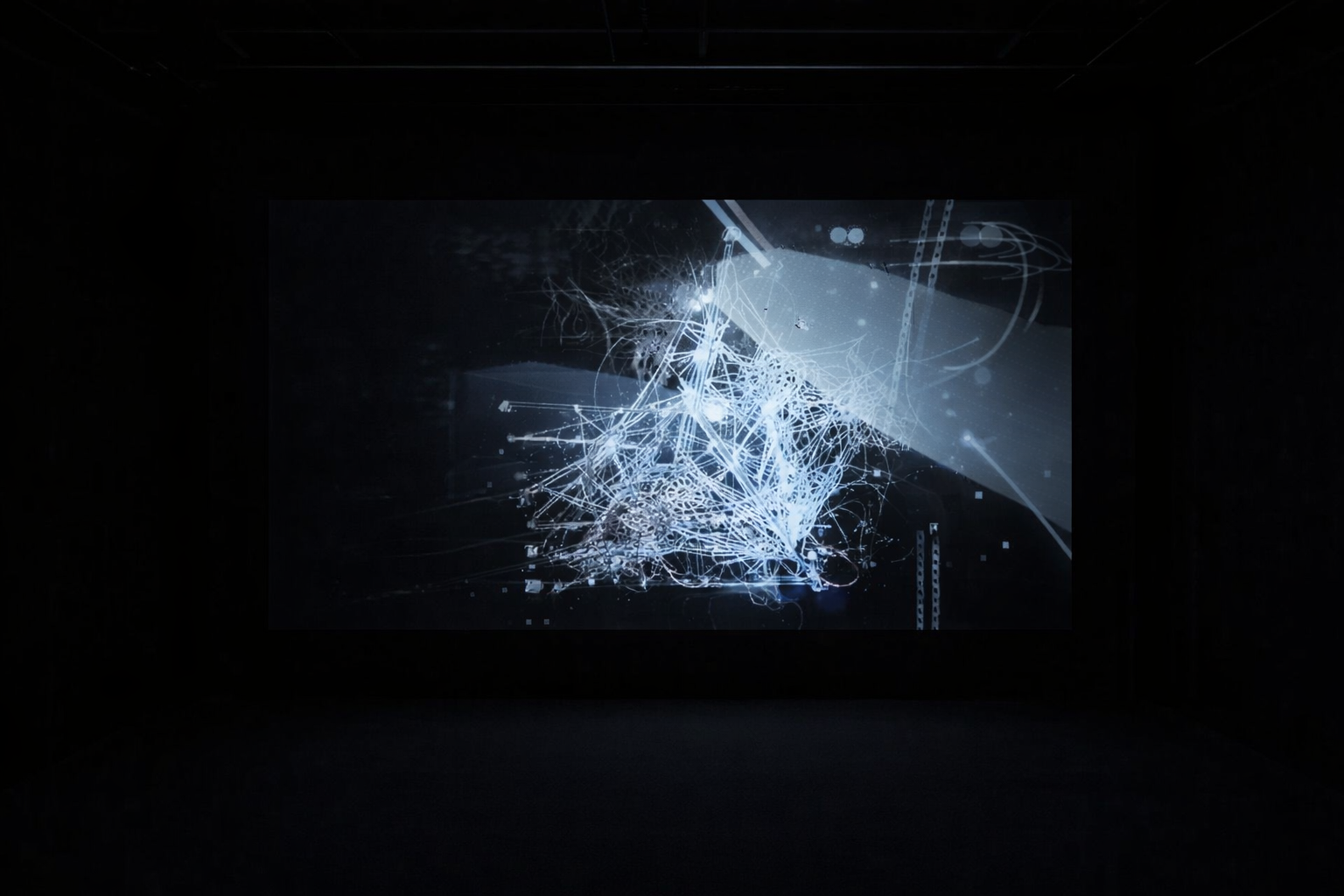

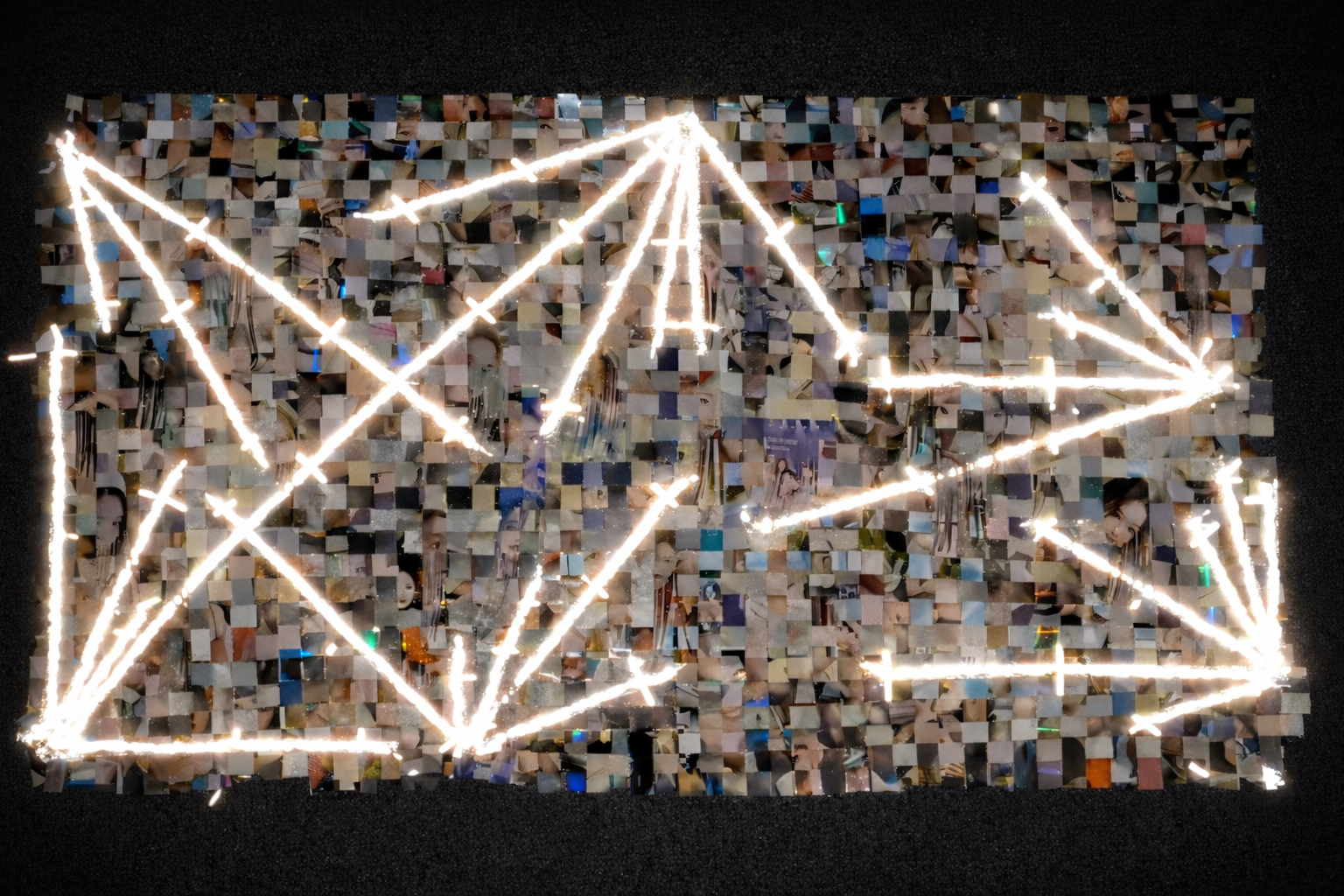

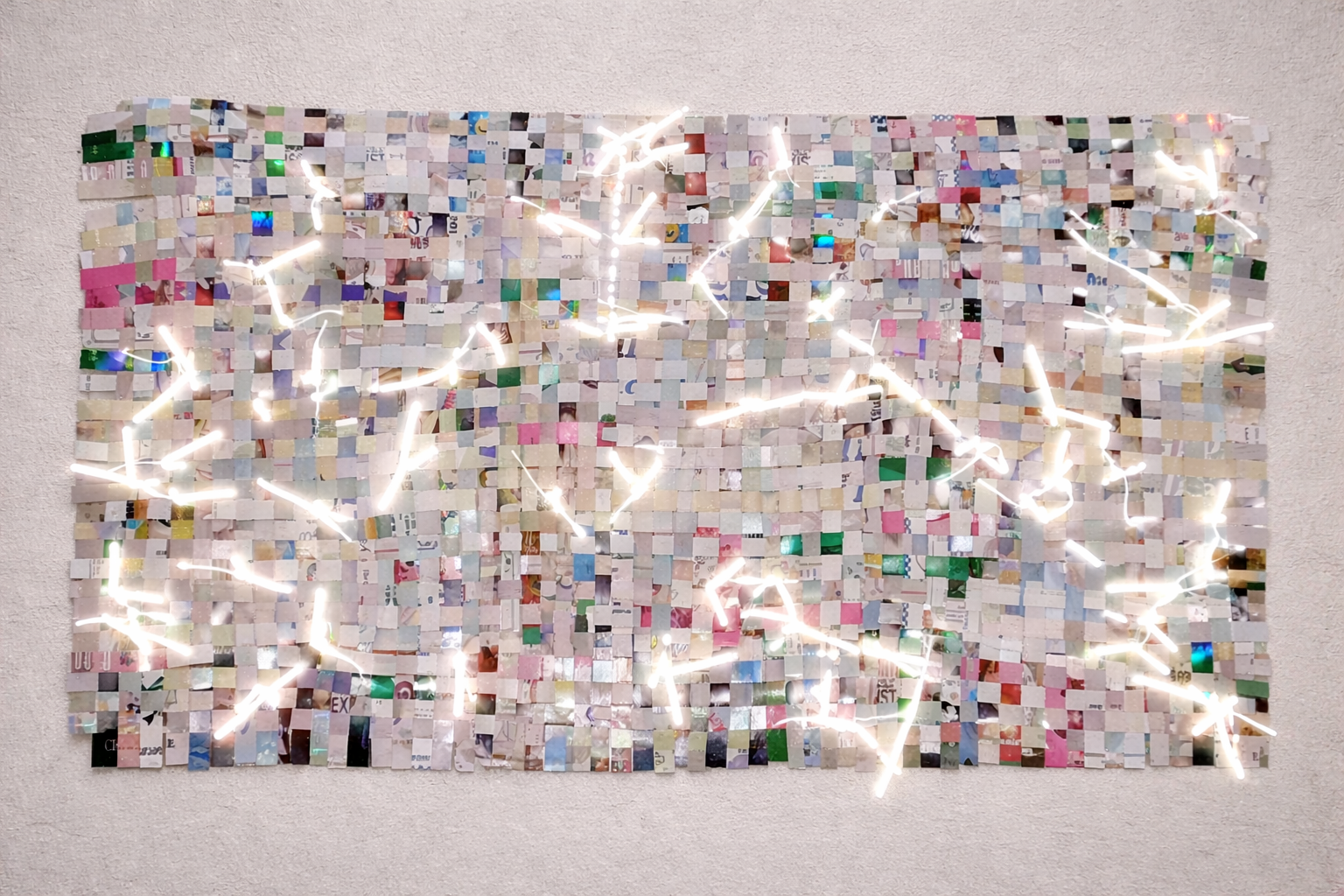

Spirit-Infusing 2024

Photo by Luan gallery

Spirit-Infusing

Shenlu’s project takes weaving as its core medium, yet it is not a simple continuation or revival of traditional craft. Rather, it stages a critical inquiry into industrial heritage, technological intervention, and the asymmetrical power relations embedded within globalization. In contemporary systems of production, many traditional crafts have been marginalized, re-coded as cultural symbols, or absorbed into technological and capital-driven frameworks. By introducing algorithmic logic and non-traditional materials, Shenlu reactivates relationships among fibers, optical threads, and structural forms, seemingly “infusing life” into matter. At the same time, this process exposes the power dynamics of technological intervention: algorithms and digital systems do not merely animate materials; they redefine what counts as life, creativity, and cultural value.

Within Western esoteric traditions—particularly Wicca and related neo-pagan practices—material arrangements are likewise understood as sites of life activation and energetic circulation. In Wiccan crystal healing systems, crystals and minerals are not treated as inert matter but as repositories and conductors of natural forces. Practitioners assemble crystal grids according to geometric principles, symbolic correspondences, and elemental logics, believing that specific configurations can channel, amplify, or stabilize energies associated with healing, protection, and transformation.

Crystal grids operate as highly ritualized systems. Stones are selected based on attributed properties, aligned with directions, planetary symbols, or elemental frameworks, and “activated” through intention, gesture, or spoken invocation. In this process, vitality is not assumed to be inherent to matter; rather, it is generated through structure, repetition, and belief. The crystal grid thus becomes a temporary organism—an energetic body whose agency emerges from the interaction between material properties and symbolic order.

Shenlu’s project resonates with these practices in its understanding of structure as a carrier of vitality rather than a neutral form. By introducing algorithmic systems into material assemblages, she echoes the logic of the crystal grid: life is not embedded in matter but produced through patterned organization. This parallel, however, also raises critical political and epistemological questions. When contemporary technologies replicate or abstract ritual systems, who defines the terms of “energy,” “life,” and efficacy? Does algorithmic intervention amplify material agency, or does it reframe spiritual concepts within a technocratic epistemology?

This question—how structure generates a sense of life—extends into the broader history of technology. The Jacquard loom of the eighteenth century employed punched cards to control weaving patterns, translating holes and threads into executable instructions. Through this correspondence, textiles acquired a form of programmed vitality. The loom exemplifies an early convergence of structure, labor, and control, revealing how life-like complexity can emerge from rule-based systems.

During World War II, the programmers of ENIAC were predominantly women, then referred to as “computers.” They performed complex calculations and structured machine operations, undertaking the most intricate and foundational technical labor. Like weavers mastering elaborate patterns, these women carried the structural intelligence of the system. Grace Hopper played a pivotal role in the development of compilers and in articulating the concept of the “bug,” yet her contributions were long underrecognized. Across both craft and technological histories, women have often been central to giving form and vitality, while their labor remains systematically obscured.

In contemporary contexts, the intersection of weaving and computation continues to provoke critical reflection. Digital life experiments, such as Thomas Ray’s virtual ecosystem (1991), demonstrate the potential for self-organization while exposing the limits of simulation and control. Neuroscientific modeling projects like the Blue Brain Project attempt to reproduce biological processes in silico, offering insights into emergence and structure, yet they also embody a modern impulse to manage, replicate, and govern life. These examples remind us that technological “animation” of matter is inseparable from social, ethical, and political concerns.

Within contemporary art, weaving is no longer solely a physical craft; it has become a site where materiality, life, and human intention intersect and collide. Projects such as MIT Media Lab’s Weaving Memory explore information storage and display within textiles. Artists including Anicka Yi and Heather Dewey-Hagborg combine biological materials with textile processes, programming, and AI to create mutable, dynamic works. The Cloud Weaving Model integrates AI with indigenous weaving knowledge, emphasizing relational and ritualized practices. Yet these experiments also prompt reflection: when technology intervenes in symbolic or traditional systems, who defines meaning, and where does authority over material life reside?

In Shenlu’s work, weaving techniques extend to optical fibers and non-biological materials. Through the interlacing of algorithmic patterns and human intervention, inert matter appears “activated.” Threads of silk, metal wires, and glass beads form structures that function as an “energy language”—not merely geometric compositions but responsive configurations shaped by material properties themselves. At the same time, this process raises questions of authorship, control, and technological limits: is the vitality observed in these structures emergent, or is it pre-defined and constrained by human and algorithmic design?

By situating weaving at the intersection of human agency, material behavior, and technological systems, Shenlu transforms a traditionally productive activity into a synthesis of spirit and craft. She frames weaving as a bridge connecting humans, nature, and the cosmos, where structures arising from the interaction of materials and algorithms express relational dynamics as much as visual form. Her practice continues a trajectory from traditional textiles to digital life, cultivating new forms of vitality while critically reflecting on the power relations embedded in technological and cultural intervention.